September 12 2022

Do you name your car? 🚘

tags: Psychology

The fascinating psychology behind our need to find the human in everything non-human.

I was recently sitting with my roommate doing homework at the dining room table when, in a string of procrastinating conversations, an interesting question was posed. As these conversations go, I can’t quite remember how we arrived at the topic, yet the question stands on its own: “Do you name your car(s)?” I was intrigued by this question because in my history of driving, naming my car has never crossed my mind—I suppose I don’t necessitate a name for a car as I would for, say, a dog or cat. Yet, as I continued talking with my roommate, I realized that naming cars might be just as normal for some people as not naming them is for me. But exactly why do people name inanimate objects? A quick google search with this query gave me a simple answer: anthropomorphism. But what exactly is that? In this article I’ll unpack this fascinating psychological phenomena as researched by leading experts in the field and reveal just how prevalent anthropomorphism is in our daily lives, from naming cars to new-age Artificial Intelligence.

You may be more familiar with anthropomorphism than you think. In its Latin roots we find a simple definition: anthro- meaning human and -morphism meaning taking other forms. So, in essence, anthropomorphism is simply non-human things taking on human characteristics. Anyone who has taken the ACT or studied literature to any degree is familiar with personification in writing, a close relative to anthropomorphism.

“Earth felt the wound; and Nature from her seat, Sighing, through all her works, gave signs of woe.”- John Milton, Paradise Lost

In this excerpt from John Milton, a common user of personification, Earth and Nature take on states of human emotion in a poetic use of figurative language. But, Milton’s rhetorical personification is just a subset of the entire anthropomorphic spectrum, a construct only recently researched in depth by psychologists.

Indeed, as you might imagine, projecting our humanity onto non-human objects has everything to do with our psychology (…and, I bet philosophers might also have a thing or two to say about this topic as well, but for the purposes of clear analytical reporting, we’ll stick to the psychologists). Nicholas Epley, Adam Waytz, and John T. Cacioppo, all leading experts in anthropomorphism, have published much of the research now canon in the field. The bulk of anthropomorphism’s history in psychology has been the study of assigning human characteristics to animals and the accuracy thereof. However, in a string of ground-breaking studies, Epley et. al shifted the focus onto us, the humans, to get to the bottom of why we anthropomorphize in the first place. The answers are somewhat simple, but actually employ the work of many sub-fields of psychology, including social, cognitive, and development psychology and even neurosciences (Epley et. al 2010).

As defined by Epley et. al, anthropomorphism:

“involves going beyond behavioral descriptions of imagined or observed actions (e.g. the dog is affectionate) to represent an agent’s mental or physical characteristics using humanlike descriptors (e.g. the dog loves me)” - Epley et. al 2007

I included this quote because it clarifies an important point. The qualification of characteristics being “humanlike” is certainly dependent on your personal opinion and perspective. But, for the context of psychological research, these nuances aren’t as important. We’ll leave the intricacies of that topic to the philosophers. For us it is only necessary to understand that humans project many of their qualities and actions (such as the act of loving) onto non-human things.

The research of Epley et. al compartmentalizes this idea by posing the psychological variability in anthropomorphism: some things are anthropomorphized more than others; children seem to anthropomorphize more than adults and further some adults more than others; some contexts and cultures evoke more anthropomorphism than others. To explain these variabilities, the researchers proposed their three-factor theory of anthropomorphism, a simple yet versatile hypothesis that deepens our understanding of why we see the human in everything non-human. The three factors are, in order of their acronym: Sociality, Effectance, and Elicited agent Knowledge (SEEK) (Epley et. al 2007). Beyond these somewhat complex terms exist easy-to-grasp ideas with hosts of research proving their accuracy. In the coming sections I will briefly explore each of these determinants of anthropomorphism, after which I will provide some much-promised modern relevance.

Sociality

This first factor of anthropomorphism is a well-defined construct in society: in lack of social connection, we fabricate it. With no doubt, and thanks to leagues of social psychology research, we know that humans are extremely social creatures with respective social needs. So, as it appears to Epley et. al, those social needs are crucial in the process of anthropomorphism within our conscience. Consider someone who is very lonely:

“One method of regaining social connection, we have suggested, is to anthropomorphize non-human agents, essentially creating humans out of non-humans. People may be especially likely, then, to anthropomorphize non-human agents when they are feeling socially disconnected” -Epley et. al 2007

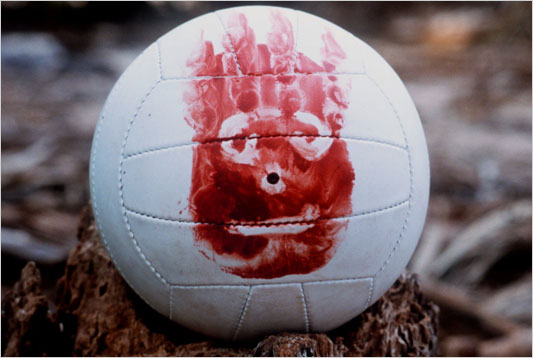

To test this hypothesis, the researchers took a survey of college students, measuring the students’ degree of loneliness against their anthropomorphic tendencies towards their pets. The results of the survey showed the predicted correlation between social disconnection and anthropomorphism—the lonelier a subject was, the more likely they were to anthropomorphize their pets. But, the sociality of anthropomorphism already held strong cultural evidence before the academic stamp-of-approval. One famous example comes from the classic movie Cast Away. When stranded on an island, Tom Hanks constructs a friend from a Wilson volleyball. Hanks’ crippling depression upon losing his friend to ocean currents shows—albeit fictional—the authentic relationships people can build with non-human objects via anthropomorphism. I would be remiss to say I didn’t shed a tear myself watching Wilson float away.

Younger readers might remember a similar anthropomorphic scene from SpongeBob SquarePants. When SpongeBob secludes himself to his pineapple in fear of the outside world, he befriends a penny, chip, and used napkin, giving each a personality—sociality anthropomorphism at its finest (not to mention that SpongeBob himself is an anthropomorphized sponge, but I won’t get too “meta”).

Effectance

This next factor of anthropomorphism, while a bit more convoluted than sociality, is equally as important. The term effectance in psychology is usually paired with motivation:

“Effectance motivation entails the desire to reduce uncertainty and ambiguity, at least in part with the goal of attaining a sense of predictability in the environment.” -Epley et. al 2007

We live in a chaotic world—this is no doubt—and thus we find ways to make sense of it all. The researchers go on to argue that anthropomorphism is one of those ways. Our deep understanding of “how to be human” spills over into our interactions with our surroundings, prompting our inner psyche to treat non-human things as humans in order to better understand them. Also, a facet of this effectance anthropomorphism is control, meaning that by projecting human characteristics onto non-humans, we can better control those things. In another survey, the researchers proved this by asking participants to watch videos of two dogs, one showing unpredictable behavior and another predictable behavior. Upon measuring the participants’ “desire for control” against their anthropomorphic rating of the two dogs, those participants with a higher desire for control showed higher anthropomorphic ratings of the unpredictable dog. The results of this study confirm that when we are confused about something in our environment, we tend to apply our honed human-to-human analytical skills to the situation.

But, once again, we didn’t necessarily need an academic study to prove what has been culturally obvious for millennia.

“The tendency to see humanlike figurers among the constellations, humanlike religious agents guiding weather patterns, or humanlike ghosts and spirits causing madness and psychological dysfunction has long been explained as a logical attempt by humans to understand and predict the complicated world around them using existing knowledge about human agents.” -Epley et. al 2007

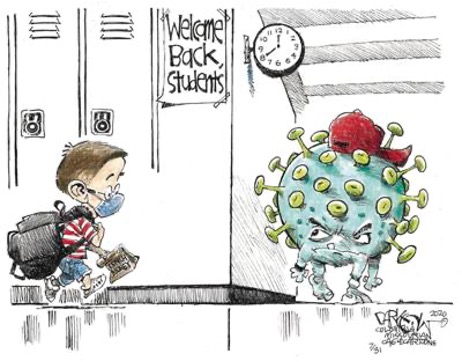

Since our beginnings we have sought to understand the mysteries of our cosmic existence via our human intuitions. Another modern example of effectance anthropomorphism is COVID-19. Much of the language used to explain the virus attributes human actions, such as “waging war against COVID” or “the virus has come back with a vengeance.” COVID-19, a non-living jumble of organic material has cost the lives of millions of people—humanizing the virus is our way to cope and attempt to control its threat to humanity.

Elicited Agent Knowledge

The last factor of the researchers’ theory is rooted in cognitive science, where the principles of our cognition serve to enhance the likelihood of anthropomorphism. Within the basic human cognitive model, we intake knowledge through our sense, process that information by activating previously stored knowledge, then act on that knowledge. Epley et. al propose that when interacting with non-human objects, humans use their stored knowledge of humans for three primary reasons. First, because we are inherently human and bound by our human bodies, we lack the knowledge of non-human objects through any other perspective but our own. Despite some convincing costumes at Halloween parties, we only really know how to be human.

Second, humans have “mirror” neurons which are activated when attempting to mimic actions perceived by things in the environment. Because we mirror our surroundings using human actions, we tend to perceive our surroundings as taking on human qualities. These “mirror” neurons are crucial to our emphatic faculties (feeling what other people are feeling), but it turns out that they do the same for non-humans.

Lastly, babies’ entire worlds revolve around interactions with other humans. It is not until later in their cognitive development that children begin to recognize the difference between what is human and non-human. Yet, it seems that the residual effects of our anthropocentric childhoods ripple into our adult lives. Certainly adults understand that dogs aren’t human, yet that doesn’t stop the tickling of our subconscious telling us to treat them like humans (Epley et. al 2007).

In short, our brains are wired to understand humans, and that’s what they do, even if what they’re perceiving isn’t always human. (The same reason why putting brownie mix into a cupcake tin will produce cupcake shaped brownies. The content of the dessert is still brownie, but they take on a cupcake shape).

Modern Relevance

So, do you have a better understanding of why you might name your car? If the technicalities of the three-factor theory of anthropomorphism went over your head, here’s the TL;DR: one might name their car because (a) they are lonely and desire human connection, (b) they are attempting to understand or control the car when faced with unpredictable behavior, or (c) they simply can’t help but see the car as human because of innate anthropomorphic circuitry in their brain.

However, anthropomorphism has much broader (and more serious) relevance than the naming of cars. Our trusted researchers, in a 2010 follow-up paper to their initial theory of anthropomorphism, laid out many topics outside of psychology where anthropomorphism applies.

One of the most prominent topics is human-computer interaction. It is clear that in today’s society, computers and smart-phones consume our attention, despite a constant debate on technology’s trustworthiness. What makes an app seem trustworthy? What makes a voice assistant more easily accessible? How should a self-driving car react to moral dilemmas on the road? All of these questions, and more, are derived from anthropomorphism: What makes a person more trustworthy? What makes a person easier to talk to? How might a human react to moral dilemmas on the road?

“Computer scientists, robotics developers, and engineers can use anthropomorphism research in their efforts to optimize technology by focusing on the consequences of anthropomorphism and also identifying the people that are most prone to these consequences” -Epley et al. 2010

What the researchers are getting at here applies to other topics as well. People are susceptible to anthropomorphism, and that can be taken advantage of. Why do cars still have headlights that look like eyes and a grill that looks like a smile? Why is the Progressive Insurance mascot an insurance package with eyes and a mouth? Market researchers know a thing or two about anthropomorphism… just look around and you’ll begin to see your reflection in many things you buy.

And finally, back to our friend John Milton. How does humanizing the earth or nature affect how we treat them? Environmental science might just incorporate a thing or two from anthropomorphism as well.

I hope you can take this knowledge of anthropomorphism with you for the next few days and make note of all of your anthropomorphic tendencies. But don’t think you need to stop by any means. After all, you are only human.

References

Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review, 114(4), 864–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.114.4.864

Epley, N., Waytz, A., Akalis, S., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). When we need a human: Motivational determinants of anthropomorphism. Social Cognition, 26(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2008.26.2.143

Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Who Sees Human?: The Stability and Importance of Individual Differences in Anthropomorphism. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610369336

Adapted from an assignment I did in a psychology course